By Guillermo X. Garcia

Ruben Mungia, a career printer, laughs as he recalls "how smart the U.S. Army was" to let him join the service in the middle of World War II, only to assign him to Randolph Field in San Antonio, his hometown, where he ran the print shop at headquarters command.

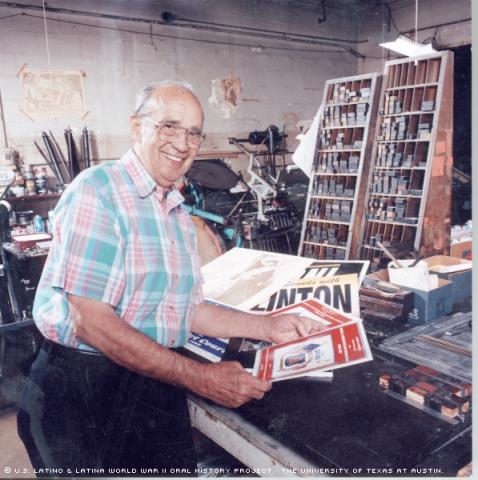

The second oldest of seven siblings, Mungia would never leave home during his active duty stint. Now a successful and heavily connected insider in San Antonio's local political scene, Mungia, a high school dropout, runs a family-owned print shop that has been operating in the same predominantly-Latino West Side neighborhood for nearly seven decades.

"I had a furlough and went home every night, so yes, [military service] was ideal for me. I had it made," the pioneering political activist said with a grin.

It was the second time Mungia had tried to volunteer. Immediately upon hearing of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he and 19 of his friends went to the downtown recruiting station to enlist.

"We went there on Sunday, not knowing that the office was closed. So we went back the next day, and 19 of the 20 childhood friends were accepted," he said. Because of a minor problem with his left eye, Mungia was rejected.

But where others might have been discouraged, Mungia tried again. He entered the Air Force in September of 1943, and, when discharged in December of 1945, was assigned to the HQ Squadron at Randolph; he’d risen to the rank of Corporal.

The single-mindedness that has guided Mungia -- for many years, he has actively promoted and financially supported Latinos for public office, as well as lobbied for more equal educational opportunities for West Side kids -- was at work even then, at age 22.

"I believe that the war spirit, a desire for battle, is inherent in all Mexican males. Besides, what was I going to do, sit around and look at girls while my buddies were over there dodging bullets?" said the no-nonsense blunt-speaking 82-year-old. Mungia, who describes himself as a "boat rocker" who doesn’t mind taking on the establishment -- whether it’s the entrenched political machine or the prevailing social current -- has made a life of speaking his mind, "and to hell with the consequences," he said.

"Those who make a big to-do about shining shoes and shelling pecans to get by. We need to forget about that era and look to all the successes [Mexican-Americans] have had since those times," he said. "Yes, we, like all other families, had to struggle, the times were not easy, but my family never thought of us as [being] poor, and I can never remember having to go hungry."

His father, Romulo Munguia, was a journalist at La Prensa, San Antonio’s successful Spanish-language newspaper, before starting the family print shop during the depths of the Great Depression in 1934. His mother, Carolina Malpica Munguia, was a school teacher whom he describes as "the first women's libber," and pioneering radio personality. She would, in 1931, become the first to host a Spanish-language program, "La Hora Estrella," a daily hour-long program examining Mexican history and culture on radio KONO.

Mungia's parents, along with their three boys and one girl, fled Mexico in the early decades of the 1900s, as the revolution that was eventually to kill 1 million Mexicans over more than a decade of fighting, began to spread across the land.

But before entering the U.S., Mungia's mother shaved her children's heads to avoid U.S. border agents from rubbing kerosene into their hair, as was the custom then, to kill head lice they assumed all Mexican children were infested with.

"There was no way she was going to allow that to happen to her kids," he recalled. "That's the kind of woman she was."

Mungia, who believes discrimination is based more on social and economic issues than racial issues, nonetheless recalls as if yesterday the one and only time he felt his ethnicity used against him.

It was post-war boomtown San Antonio, and he and his wife Martha, who married in 1945 after he left the service, were looking to buy land to build a house.

"We found the place we liked, filled out all the forms and we were told the deal had been accepted. The next day, the sales promoter asks about my name, he said he was not familiar with the name, and asked what it was.

“I said, proudly, 'I'm Mexican,'" Munguia recalled.

"All of a sudden, the guy said there was a slight problem with the paperwork and could he call me back?

"I said, 'No, you so-and-so. I know what you are doing, not selling to me 'cause I am Mexican. To hell with you.' And I called off the deal."

It was that incident that would make Mungia decide to join such groups as LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens) and the American G.I. Forum, which were founded to promote Latino interests and openly denounce racial discrimination.

It was what Mungia calls the more subtle instances of discrimination that led him in 1950 to be among a small group of businessmen -- he was the only Hispanic -- to promote Henry B. Gonzalez's first attempt to become a state representative in Austin.

Gonzalez, a legendary San Antonio politician, was the first Latino to serve on the city council. He was later to be elected to Congress, where he represented the Alamo City for more than 30 years.

Mungia, Maury Maverick, Sr. and other prominent power brokers backed a ticket of three candidates, including Gonzalez, against the wishes of the establishment Democratic Party in the 1950 elections.

"The [Hispanic] West Side overwhelmingly backed the slate, but the (Anglo) North Side wasn't ready yet to vote for a Mexican."

The slate won, except for Gonzalez, who lost in a runoff. But Gonzalez, with Mungia's help, would run again and win, becoming the first Latino to serve in the state Legislature.

"That first race served notice. It convinced the Anglos that we were joining the political battle and that we would stay in it."

For 50 years, that activism has led him to Washington and Austin to forcefully press for equal rights for Hispanics. His sister is Henry Cisneros' mother, and he has heavily promoted Cisneros and the next generation of Mexican American politicians as actively as he once promoted Gonzalez

Although in his 80s, he remains tuned in to the political current, joining professors, business people and politicians at the "Snakepit," a Saturday morning coffee klatch at Mi Tierra Restaurant, "where we drink coffee, tell each other lies and solve the world's problems."

The experiences he and other Mexican Americans had in the war would serve as a catalyst for significant social change upon their return to civilian life.

"The war changed us a great deal. We came back with different ideas. For me, it gave the confidence, as a corporal, to make decisions and not fear colonels and other officers," said Mungia, adding that Mexican American soldiers "saw the world and came in touch with other peoples -- Italians, Jews, Russians" and Poles -- who would serve as role models.

"We came back from that war with the knowledge that we had fought the greatest army in the world and defeated them," he said. "For Mexicans, that meant that we came back no longer satisfied with the church's idea that the meek would inherit the earth. We came back with the idea that we want our piece of the earth NOW."

Mr. Munguia was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on November 11, 2001, by Martha Treviño.