By Stephanie De Luna

Growing up in Phoenix, Rudolph “Rudy” Lopez knew that he was destined to serve in the military. Born in 1946, Lopez grew up in a close-knit family with a long line of military war heroes.

“We were very much an all-American family. The military was just something that you do. That’s all there was to it,” Lopez said.

Lopez’s father was a member of the Army military police during World War II in France.

“My dad didn’t have much of an education, but as far as I’m concerned, he was second only to Jesus Christ,” Lopez said. “My dad was a super, super guy.”

Lopez’s brother also served in the 82nd Airborne Division in the early 1960s. And, almost all of Lopez’s uncles from both sides of his family served in WWII, after which several of his cousins served in the Korean War.

Lopez grew up in a proud Latino community. His parents, Joe Lopez and Frances Hidalgo Coronado Lopez, raised four children. Lopez lived between his tío Nacho (his father’s brother) and his tío Luis (his mother’s brother), and there were about 15 cousins living between those houses.

“There was a lot of family unity,” Lopez said. “We had very Chicano traditions. We ate menudo…tamales.”

Menudo is a spicy soup made with cow’s stomach, hominy grits and spices. Tamales are corn dough, which has been filled with different types of meats or even sweets, wrapped in corn husks and steamed.

Lopez had a passion for sports from an early age. In grade school, he played football, baseball, basketball. He was undefeated at Phoenix Union High in wrestling during his senior year.

“Being involved in school activities kind of got us away from the street kids who were smoking marijuana, stealing and doing bad things,” Lopez said. “We were more geared to staying out of trouble so we could be involved at school.

“I learned very young that I had to follow the rules,” he said.

After he graduated from high school in 1964, he began attending Phoenix College. However, in January of 1966, he talked to some of his friends about enlisting in the military. Knowing that he might get drafted, Lopez volunteered.

“My family served honorably,” he said. “My country was in trouble, so it was my turn.

“I didn’t know anything about the war except that North Vietnam was Communist and the South was fighting for its independence, and the U.S. was on the side of the South, trying to help them gain their independence,” he added. “That’s all I needed to know.”

Although the men in Lopez’s family had a tradition of going to war, it was still hard for Lopez’s father to see his son leave.

“When I left home [for]Vietnam, I saw him cry,” said Lopez. “That’s the only time I saw him cry.”

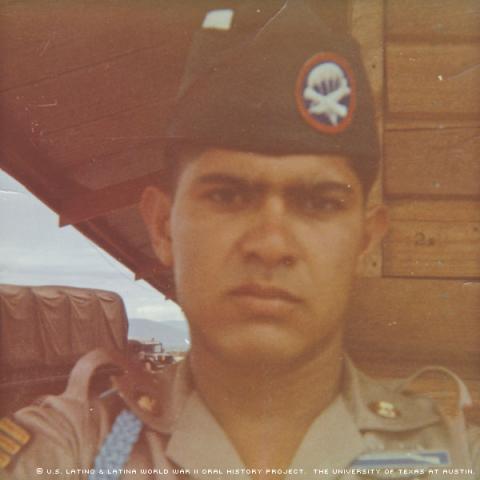

After basic training, Lopez went to Fort Campbell, Ky., in June 1966 with the 101st Airborne Division in the Battalion Headquarters, where he did mostly clerical work – and he was not satisfied with his comfortable job. He wanted to see combat and volunteered repeatedly. On his fourth attempt, he succeeded in getting orders to go to Vietnam. He arrived there in November 1966.

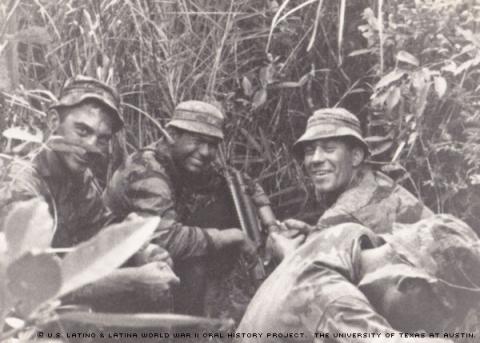

In Vietnam, Lopez was a Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol ranger, a member of an elite group that would work in five- or six-man teams and live in areas of operations where there was a known enemy group. Once they found the group, they would make observations to report back.

“We knew very little about jungle warfare. It was very scary. You don’t sleep at night. You can’t talk,” Lopez said. “We did something that almost nobody wanted to do. It was extremely dangerous. That just made us more unified. We were closer, and it hurt a whole of a lot more when one of us got hurt or killed.”

There were two other Latinos on his team: Rey Martinez and Freddy Hernandez, a Cuban-American. There were also a couple of African-Americans. He and Martinez were particularly close.

“Rey and I palled around together because we were Chicanos -- not because we wanted to be separate from others. … It was great speaking Spanish with another guy,” he said.

On May 19, 1967, Lopez found out how dangerous his job in the Army actually was.

“There were three of us. Ronnie was the team leader, Jimmy Cody was the point man, and I was the medic and radio operator. We had two engineers with us,” Lopez said.

Lopez’s unit was on the top of a hill and on the way down, the lead engineer tripped a booby-trap bomb and it exploded. Lopez recalled being the last man in line and seeing his entire unit fly up into the air. “I tried to get on the radio, but the bomb blew off my handset. My aid kit blew off as well,” Lopez said.

He tried to get up to help the men in the group, but he fell down.

“I thought, ‘I’m hit,’” Lopez said. Although he was wounded, Lopez went to save his comrade, and recalled Ronnie’s right leg as looking like “hamburger.” Lopez treated Ronnie’s leg as best as he could, and moved on to the other men.

The second engineer who was with Lopez’s team went into shock and started running. Lopez had to sit him down and put a stick in his mouth so he could breathe. Cody’s finger was blown off, and his arm was wounded. Lopez went to the lead engineer, who was crawling.

“I saw him and he was faced down and he started to crawl. The upper torso was moving, and his lower torso didn’t move. He was blown in half,” Lopez recalled. “I went up to him and he looked at me and started calling for his mom, and he died there.”

Lopez was severely wounded as well. His right lung collapsed, and he had holes all over his chest. There weren’t any choppers in the area, so his team couldn’t evacuate until a chaplain’s chopper volunteered to come down. Ironically, Lopez always received communion from that chaplain, and Lopez would always tell the chaplain that he wanted to be a CA (chaplain’s assistant).

“The first man off that chopper was him, and I told him, ‘See chaplain, I told you I wanted to be a CA,’ ” Lopez said.

Lopez recalled that he felt well cared for, with about 15 medics working on him.

“That’s a hell of a job that they had to do,” Lopez said. “The doctors, nurses, medics and people who worked at the aid station,- they’re the greatest people on earth.”

After he was wounded, Lopez was sent to Camp Zama, Japan, where he spent six months in the hospital.

After several surgeries, Lopez volunteered – and was sent back -- to South Vietnam.

“I went out to the woods on a couple of missions, but it wasn’t the same anymore. My mind wasn’t there. I was more afraid. I was still doing my job, but I told myself that, if I flinched just once, I would get someone killed,” Lopez said. For his safety and his unit’s safety, Lopez decided to work over the radio operations in the back and help out the new Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol servicemen.

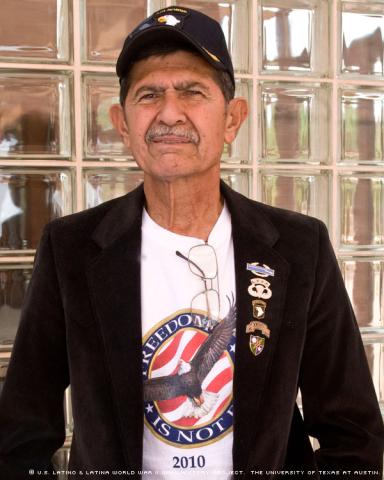

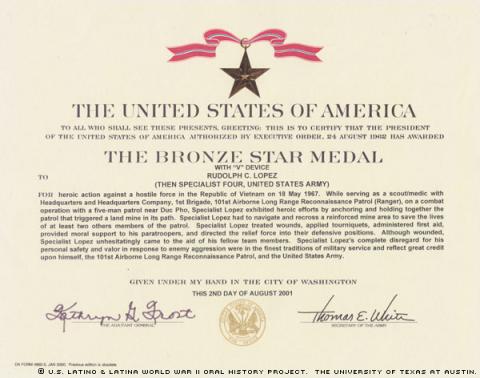

Lopez returned to the United States after Christmas of 1967. He was discharged in December 1968, at the rank of staff sergeant. He was awarded a Purple Heart, and he initially refused to allow others to pursue a Bronze Star for him. It was not until 2001 that Lopez received a Bronze Star with V Device for valor. He said he had previously not wanted the medal because he felt that, as a medic, he was just doing his job.

But, at the insistence of one of his daughters, Cynthia Yvonne, and with the help of friends who endorsed his being awarded the medal, he finally received it.

“I think it’s pretty neat! I saved two peoples’ lives, and they are the ones who pushed for it. It came from my peers, so that’s why it’s meaningful to me,” he said.

And his grandchildren think it’s cool.

On the official Army certificate authorizing Lopez’ Bronze Star, he is credited with “anchoring and holding together the patrol that triggered a land mine in its path.

“Specialist Lopez had to navigate and recross a reinforced mine area to save the lives of at least two other members of the patrol. Specialist Lopez treated wounds, applied tourniquets, administered first aid, provided moral support to his paratroopers, and directed the relief force into their defensive positions.”

But when he returned home, he said, there was a long period of adjustment caused by post-traumatic stress disorder.

“When I first got home, I couldn’t sleep in a bed,” Lopez said. “My parents would find me behind a sofa. I would go somewhere where I felt safe.”

Wanting to have a normal life again, Lopez married his first wife, Jessie Chavez, and they had three children: Catherine Frances, Cynthia Yvonne and Rudy, Jr. His wife stood by his side while Lopez recovered mentally and physically. He was sent to a mental ward a few times as well.

“The kids saw a lot. They suffered a lot too,” he recalled.

The police were called to Lopez’s house a few times. Once, they had him surrounded because he had a shotgun and was going to shoot. His friend, Oscar Cota, who had served in Korea, talked him out of it.

Lopez also drank heavily.

“It [the drinking] was not casual, but I wasn’t an alcoholic,” he said. “I came close though. …. It came to an end about 20 years ago when I finally said, ‘I’ve put my body through enough, and it’s about time to take care of myself.’”

Lopez was divorced from his first wife about 20 years before his interview, and 10 years later he married Lucy Gonzalez.

Determined to improve the life of his family, Lopez went back to school at Phoenix College and Arizona State University, where he studied engineering, although he said that he did not receive his degree because he had to work to support his family.

He got a job at the Department of Transportation, where he worked on a survey crew and as a drafter and roadway designer for 12 years. Lopez then began working in the private sector primarily designing roads for Mann & Johnson, where he was quickly promoted.

“I never had to fill out an application or resumé. The word got out pretty quick about who I was,” Lopez said. “I was very fortunate.”

He then worked at Coe & Van Loo, an engineering company, where he was in charge of a design crew.

“It was rough because I was the only civil engineer in a command position without a degree,” he said. He felt that he had to prove himself more than non-Latino whites did.

“I had to work twice as hard. I made a good name as an engineer. Finally, everyone came around and realized that I knew what I was doing, and that I wasn’t a token Chicano,” he added.

Lopez retired when he was 50 because he needed more surgeries due to his wounds from Vietnam.

“Because of my internal injuries I have a lot of adhesions that grow inside and wrap themselves around my intestines and, when I get nervous or high-strung, they tighten up and choke off my insides, and it’s extremely painful,” he said. “I’ve had surgery for that and a bunch of other surgeries.”

Still wanting to contribute to society, Lopez became involved in veterans’ organizations, such as the Military Order of the Purple Heart, The American Legion, Disabled American Veterans and Veterans of Foreign Wars.

“I am very involved politically now. I tell my kids, make your own decisions, but you need to know as much as you can before you can make a good decision,” Lopez said.

“In my opinion, Vietnam was the first living-room war,” he said.

He believed that when politicians started seeing the war on television, they started making changes and forming other opinions about war.

“It should be mandatory that politicians send some of their family members out to war,” Lopez said. “How many times would they vote for war then?”

Lopez also believed that Vietnam left an imprint on Latinos and that their service should be recognized nationally.

“It should be known in the United States that we did our part. We shouldn’t have to be beating the same drum on our own telling people what we did,” Lopez said.

“I’ve had a lot of things thrown my way to make me stumble. And I’ve stumbled and I’ve fallen, but you have to keep getting up, brush yourself off, take two salt tablets, and drive on,” he added.

(Mr. Lopez was interviewed on Aug. 16, 2010, in Phoenix, Ariz., by Valeria Fernandez.)