By Frank Trejo

Growing up in Southern California, Rudy Acosta was like countless of other young boys. He escaped each week to the movies and watched the likes of Errol Flynn and John Wayne triumph over the bad guys.

Little did he know that just a few years later, World War II would propel him into the midst of one of the biggest confrontations the world has seen. Acosta, the son of Mexican immigrants, would find himself in the center of numerous heroic escapades.

"In my case, I lived that... We lived that experience," he said.

During a recent interview at his home in the Los Angeles area, Acosta, now 77, spoke with a sense of amazement and wonder at the events that led him from humble beginnings, to serving as a gunner on American bombers. He described the nightmare of flying into thunderous flak that protected enemy targets, the rush of firing his machine gun against German fighter planes, and the sadness of watching U.S. planes, some carrying his friends, shot down in flames.

Acosta's memory, not just of World War II events, but of much of his life, remains razor sharp. His life, which began on the U.S.-Mexico border, has taken many turns. He has worked a variety of jobs from cab driver to ditch digger, to construction supervisor. More recently, he has worked at a local racetrack. After the war, he married and raised three children.

There is no question, he said, World War II changed his life.

"I think I aged 10 years in knowledge in those three years (of the war)," Acosta said. "All the places I was stationed at and all the things I witnessed and the things I saw, I would never have been able to learn if I had just stayed home."

Acosta was born in 1923 in El Paso, Texas. His parents emigrated from Mexico to the border town before the turn of the century. He recalled that his mother worked for the Acme Laundry and his father for the railroad. His father also was a weekend matador, going across the Rio Grande to Ciudad Juarez on Sundays to fight bulls.

"That's the reason my name is Rodolfo, Rudy, I was named after a famous Mexican bullfighter of the time," he said.

One of seven children, five boys and two girls, Acosta recalls that he was just 11 years old when his parents divorced. After the divorce, his mother moved the family to California. It was the height of the Great Depression and jobs were hard to come by. Before they even settled down, his mother accepted a job as a fruit picker in the Gilroy area. So the Acosta family camped out with other farmworkers by night and by day picked fruit to be dried into prunes.

The family was paid $1.90 for each ton. After six or seven weeks, his mother had saved about $350, enough to bring them back to Los Angeles, rent a house and buy them all new clothes to start school.

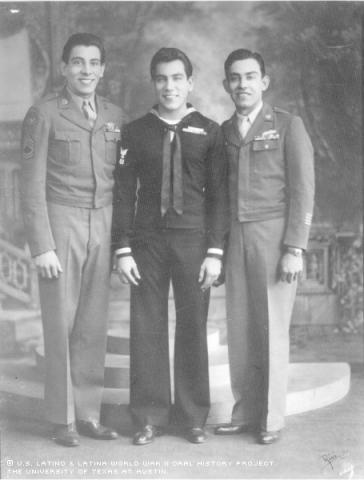

He was still in high school, and working in a downtown cafeteria when he heard the news that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor. He used to watch the newsreels at the movie theaters, fascinated by developments that seemed so far removed even though his brothers had been drafted in 1941.

Acosta remembered that his mother wanted him to quit school while he was in the 10th grade, to help the family out financially. But, he was able to convince her that he should remain and was the only one in the family to get a high school education.

He was working at Lockheed as a machinist in 1942 when he was drafted.

"I was afraid I was going to end up in the infantry," he said. "I remembered the old movies you see with the guy sloshing through the mud and the foxholes. I said, 'that's not for me.'"

Luckily, he learned that the battery of tests he had taken for several days, resulted in his assignment to the signal corps, attached to the Air Force. Five days later, he was in Atlantic City, NJ, waiting for basic training. He soon was on his way to Kansas City, Mo., for 20 weeks of radio school and then to Fresno, Calif. It was there that he decided to apply for gunnery school and was accepted.

He then trained at Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas, Nev., learning how to defend B-17 and B-24 bombers.

That is how he, after a trip via Brazil and Africa, ended up in Italy in April 1944, at the height of war in Europe. His first mission was on a bombing raid to Budapest, on Friday, April 13.

He recalled with excitement seeing the bursts of fire from the guns of enemy fighters. But, he added, that facing the fighters paled in comparison to the intense anti-aircraft flak that often protected targets.

"This is what scared the hell out of me more than the fighters, those bursts of flak that get so close and sounds like lightning when it hits next to your house... I hated flak," Acosta said.

He still has two pieces of flak that brushed past him as he hunkered down in his gun position.

To this day he recalls the prayer he used to say as his plane approached the target:

Dios nos a de cuidar y Maria santisima, y la sombra del senor San Pedro nos cubra a todos.

(May God and the Holy Mary protect us, and the shadow of St. Peter cover us all.)

"My mother used it all the time, especially when she was afraid of lightning and thunder back in Texas when we were kids," Acosta said.

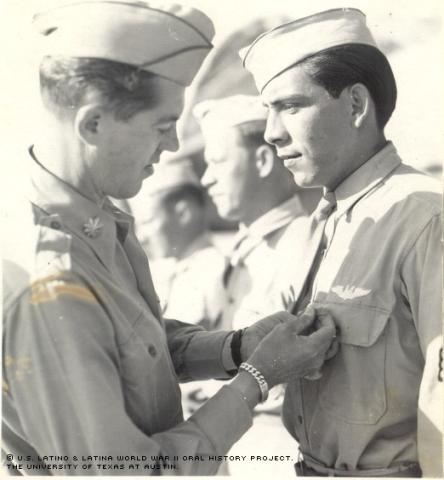

After 36 missions, Acosta earned the right to go home. But, because the fighting had intensified in Europe, he had to wait for 30 days in Naples before a ship could bring him back home.

He recalls the scene as his sister, Chelo, opened the door and saw him for the first time. Then his mother followed her to the door.

"To this day, it has never left my mind.... I remember it like it was yesterday," he said.

After the war, he took on an assortment of jobs before settling in a construction job that he held for about 25 years. But when his boss died, the business closed and he found himself unemployed. He then began working at the Santa Anita Race Track, where he continues to work, checking to make sure people entering the clubhouse and box seats area have the proper stamps on their hands.

His life, Acosta said, has been considerably different from that of his own children and even more than those of his grandchildren.

"I was 16 years old before I knew what a malted shake tasted like," he said. "At school I couldn't afford a dime to buy a hamburger they used to sell there."

Acosta also recalled that the only real discrimination he experienced occurred after his service in the war. Once while still in the Army, he and some friends were refused service at a restaurant in Lubbock, Texas.

"There's always going to be, like there is now, a minority that will always suffer indignation, discrimination and all that stuff," he said. "But it's up to the individual to rise above."