By Joel Weickgenant

Salvador Aguilar remembers lonesome nights aboard the cargo ship he served on during World War II. On many nights, he and fellow sailors and troops were forced to lie in the dark, ordered not make any sounds. It was frustrating -- the trips across the Pacific were long and the troops were often prohibited from engaging in conversations that could be picked up by Japanese submarines swimming the waters like sharks.

Loaded with troops and supplies, the ships were often the target of Japanese submarines whose primary goal was to torpedo the boats and sink their precious cargo. Any loud noise aboard ship could prove fatal, Aguilar said.

"Everything was pitch black. No radio, no nothing," recalled Aguilar, a member of the U.S. Navy's Construction Battalions, otherwise known as Seabees. "Everything had to be silent because the submarines could pick up any kind of sound."

The stillness of those moments created a great deal of tension among the sailors. "You're just waiting there," Aguilar said. "You're praying, wondering. If a torpedo hits the ship, which side will it hit?"

His battalion was responsible for constructing temporary cities on islands captured by American forces. He remembers setting up hospitals, officers' quarters and landing strips on islands, including Iwo Jima, during the war.

What Aguilar remembers most fondly are the times his unit enjoyed its R&R. He remembers nights swimming on Waikiki beach in Hawaii and visiting the bars in Honolulu -- even though he didn't drink.

One of his best memories is of listening to Saturday night jazz sessions, performed primarily by black military men.

"They segregated the black people," Aguilar said. "There was a big fence that divided where we [Hispanics and whites] were, and on the other side, where those guys [blacks] were."

"We didn't care anything about segregation," Aguilar said. "We didn't even know why that fence was there!"

But on Saturday nights, he says the sweet sounds of impromptu jazz jams would float over from the other side of the fence. Sailors would actually jump the barrier to hang out together.

"All the brass [officers] ... they would celebrate too," he said.

The jazz music sessions and the pristine beaches of Hawaii were a stark contrast to the war that was raging in the South Pacific. During the long days spent at sea, anxiety levels ran high; there was always the fear of getting torpedoed.

It was during these moments that Aguilar says he most often thought about his family back in San Antonio, Texas. The Aguilars were dutifully involved in America's war effort during World War II: Aguilar’s brother, Joe, served in the Army for a short time before he contracted malaria and was sent back home. And four of Aguilar’s five sisters worked as "Rosie the Riveters," laboring as welders for a company that produced sheet metal for the war effort.

Aguilar says he and his siblings remain proud of the service they provided for their country.

"We used to talk about it," he said. "My sisters didn't realize what I did, and they would ask me questions."

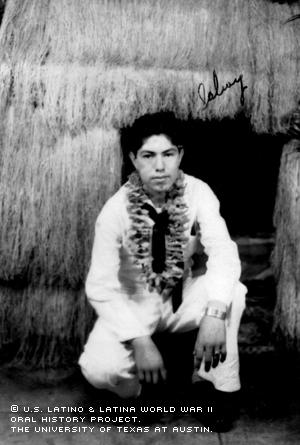

Aguilar enlisted in the Navy Seabees at the age of 15. He gained enlistment by doctoring his birth certificate to say he was two years older.

"My father passed away when I was 5 years old," Aguilar said. "I was going to school; we were living as best we could."

But while living wasn’t easy for anyone during the Great Depression, he says it was particularly rough for his mother, Consuelo Villanueva Aguilar, a young widow trying to raise seven children on her own.

According to Aguilar, Social Security only disbursed $3 a month for each child to his mother. So the kids had to work to supplement her income.

Aguilar worked at Walter's Drugstore in his neighborhood in San Antonio. At the age of 9, young "Salva," as his siblings called him, made deliveries for the drugstore from 4 p.m. until 9 p.m., all while attending school during the day.

He remembers how his sisters used to shell pecans for a dollar a day. He says they’d bring buckets of the nuts home, so the rest of the family could help out and they might get paid a little extra.

In 1943, Aguilar was still going to school, but Consuelo was struggling to support her children. The family's circumstances were so dire, military service essentially became Aguilar’s only option, he says.

So he bought a copy of his birth certificate for a quarter and changed his birth year from 1928 to 1926. He then went to his mother to obtain her signature for the enlistment papers.

"I told her I didn't want to go to school anymore, and she needed my help," Aguilar said.

A couple of days later, he found himself undergoing basic training at Camp Paul Jones in San Diego, Calif. In January of 1944, he was shipped to Pearl Harbor to begin his service with the Seabees.

Seaman First Class Aguilar was discharged from the service March 23, 1946, while at Camp Wallace in Texas. He immersed himself in civilian life immediately, he says, working as a warehouse specialist in San Antonio.

Later that year, he married Herminia R. Aguilar; they had two daughters: Mary Louise and Gloria. The couple later divorced, and Aguilar married Sylvia Aguilar in 1953; they had three sons: Salvador Jr., Roland and David. Today, Aguilar has seven grandchildren.

Looking back on the years, Aguilar says he has never forgotten the way the military turned around his life.

"When I saw my father laying in that casket, right there and then I knew I was never going to have that fatherly figure in my life," Aguilar said.

He says he made a vow at that moment to respect and learn from those older than him. And in the Navy, he had a great many to learn from, he says.

"Everybody was older than me, and I just listened," Aguilar said. "Military life to me was just that: listen, and do what you're told."

He says he has tried to instill that same level of respect in his children and grandchildren, and that if it were up to him, every young person would get a taste of what military life is like.

"If my mother hadn't agreed and signed for me to go to war, I don't know what would have happened with my life," Aguilar said.

Mr. Aguilar was interviewed in San Antonio, Texas, on October 25, 2003, by Joel Weickgenant.