By Cheryl Smith

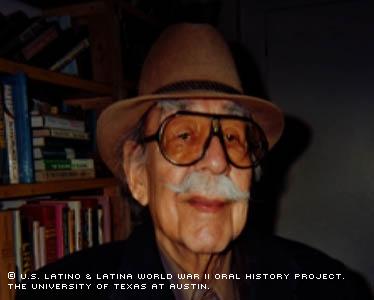

Looking at the elderly man in the brown fedora and navy blue dress coat, preening his snowy mustache with a miniature comb from his shirt pocket, one would never suspect the turbulent road he has followed throughout his life.

Teodoro Franco was unaware of battles raging overseas before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. He wasn't supposed to get drafted, he said, because he had a bad back; however, he entered the Army in 1942 without protest.

"That's part of growing up. You're supposed to do what the country tells you to do," said Franco, who was born and raised in El Paso, Texas.

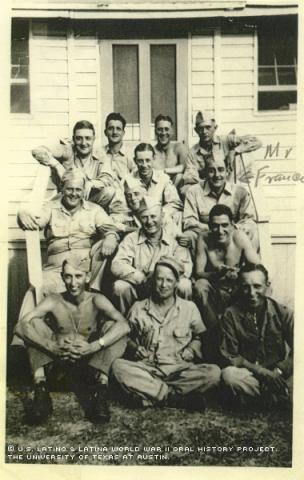

After basic training at Texas’ Camp Walters, Uncle Sam shipped him off to New Guinea. He thought about the young El Paso men of Co. E's 36th Division, almost all of whom died serving their country in battle. Many of the men were friends of his older brother, Raymundo Franco, a fighter pilot during the war. A few of the dead had been friends of his own. They were all like him -- poor Mexican Americans.

"All probably left with $1,000 in their pockets combined," he said.

During the long 29 days he went without seeing land, he kept wondering "if we'd ever come back."

There were few Mexican Americans in the 4th Army. After only a few days of being in the service, he got into a fight with a fellow soldier in the shower because he told Franco "wetbacks" couldn't be trusted because they tend to back stab.

"Here's one who will knife you in the back, and I knocked him on his butt," Franco said.

Fortunately for Franco, his lieutenant, a Jewish man who perhaps understood racial bias and who sympathized with minorities, told him he'd look the other way.

This wasn't the first time Franco had been involved in such an incident: In grade school, when his teacher slapped a fellow classmate for speaking Spanish in class, he threw the instructor to the floor, he said. His mother, who didn't know English, somehow managed to keep him from getting kicked out of school.

Franco eventually made it all the way through high school; then came the war.

He was in combat only once in New Guinea. "Just enough to scare the hell out of [me]," as he put it.

He survived four subsequent, short battles in the Philippines and managed to escape injury.

In 1946, Franco received his discharge papers at Fort Bliss in Texas. His final rank was Sergeant.

"And that's how long I've been trying to get a pension," said Franco, who claims he never received all of the federal veterans benefits to which he's entitled.

He returned to El Paso "more on guard," as a result of his battle experience.

"I saw a lot of things. [It was] very uncomfortable," he said. "You don't know what to expect."

His more high-strung self was difficult for his first wife to take, as he put it. The couple had three children -- Ted Jr., Judith Ann and Michael David -- before their marriage ended in divorce.

One would never know that Franco, an auto dealership salesman, was, at least according to him, the first person in the El Paso-New Mexico region to offer automobile financing services across the border in Mexico.

He worked on commission and never received benefits, he said. Franco thought about becoming a lawyer some day, but soon lost sight of that dream due to financial restraints.

"I started working and making money and I didn't know how to save it," he recalled.

Franco met Monserrath Gutierrez, a Mexican-born U.S. citizen, while she was shopping for a car.

"When they brought her in the office, it was love at first sight," he said.

Even today, one gets a sense of the charm he must have switched on that day when he met his intended.

Today, the married couple lives in El Paso.

"Battles are not won. Nobody wins anything," said the 80-year-old, when asked if he has any words of wisdom for members of less-seasoned generations. "People should talk about things like that every day."

Mr. Franco was interviewed in El Paso, Texas, on February 2, 2002, by Andrea Shearer.