By Sarah Carter

Thomas Casso took off through the jungle after lighting a smoke signal that would tell United States troops where to target the Japanese, who were trailing his company on Bougainville in the Solomon Islands.

Casso recalled his superior telling him, "Look, here's a smoke pot ... after we're out of sight and you can't hear us anymore -- 15 minutes -- you stay here then you light it and then you run ... and catch up with us.”

"Oh, 15 minutes can be a long, long time," Casso said.

After about that time, he remembers hearing the enemy coming, so he lit the smoke pot and took off to catch up with his troops as he’d been instructed to do.

"It started smoking and I ran like the devil. Well, I was about two or three hundred yards away, I don't know, and I realized I didn't have my rifle," Casso recalled. "I said, 'I have to go back for it. I'll get court marshaled.'"

He wonders what would have happened if the Japanese enemy had captured him.

"That was our greatest fear, because they'd butcher you up," he said.

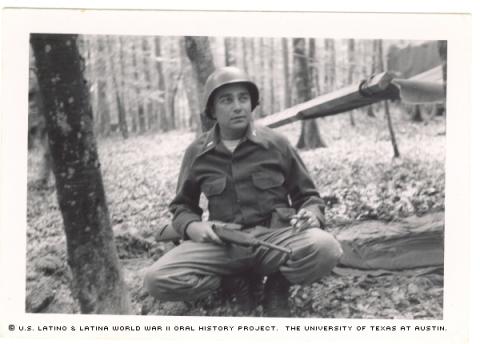

Casso spent between two and 2 1/2 years on the Pacific front during World War II.

"[My mother] prayed for me [while I was in the war]. I think maybe that's one of the reasons I'm here, you know?" he said. "She was a real believer."

Born in Chicago and raised in El Paso, Texas, Casso volunteered for the Army because he thought it was patriotic. He says he wasn’t afraid; he felt he was doing his job as a citizen.

After attending boot camp at Camp Cook in California, now known as Vandenberg Air Force Base, Casso received training as a rifleman at Fort Ord in California. When he went overseas, he was sent to Fiji as a replacement for men lost in battle at Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. His first actual battle experience came in Bougainville.

Casso says his time in the Pacific left him with both physical and emotional scars. The oppressive heat and poor water quality brought on jungle rot, an infection that can be life-threatening. He had it on his hands and feet, which caused him to lose his nails. He also contracted malaria from the swarms of mosquitoes that dogged him and the other soldiers.

When he talks about being a scout in the Army, and how he had to leave some of his fellow scouts behind when they got killed (they were the first out and typically the ones who got shot), he gets choked up.

"As old as I am, I can't forget it," said Casso, adding that nightmares and flashbacks have haunted him for years.

As a member of the 182nd Infantry Regiment, Casso fought in the Philippines: in Leyte and Samar. While he was in the Philippines’ Cebu, the Japanese surrendered to his regiment.

After two months in Japan, at the end of 1945, Casso was sent Stateside to Fort Lewis in Washington.

When he and the other GIs disembarked , Casso recalls the Salvation Army was handing out donuts and cartons of milk, which he hadn’t tasted in more than two years. He has never forgotten the small kindness of the Salvation Army.

"We [Casso and his wife] donate everything we're going to give away to the Salvation Army," he said.

Although Casso was discharged Dec. 8, 1945, at the rank of Staff Sergeant, his military experience didn’t end with WWII. He reenlisted for the Korean War and was on active duty for 10 months.

After WWII, Casso used the GI Bill to get a bachelor's degree in history from Texas Western University (now the University of Texas at El Paso). He also got his master's in public administration from Pepperdine University, in Malibu, Calif. Later, Casso earned a law degree from South Texas College of Law in Houston.

Casso spent his post-war years as a district parole officer in El Paso and as a personnel director for the city of El Paso (as director of the water and power section of the city). He finally retired as a teacher and administrator of public schools in California in 1990.

Casso also volunteered to work for the Democratic Party and ran for city councilman in El Paso and Fountain Valley, Calif.

In 1948, he married Lillian Palafox, a native of Chihuahua, Mexico. The couple had two children: Adele and Thomas.

He reflects with contentment on his service:

"I'm glad that I served. I wanted this country to be an example for all the rest of the world," he said.

Casso expressed hope that within the States, equality would continue to strengthen for future generations: "We're not a democracy yet, we're becoming a democracy, we're working on it. I want to see it someday, where, yes, anybody of any race or color, creed or religion can get the same benefits and respect from the Anglo."

Mr. Casso was interviewed in Fountain Valley, California, on July 2, 2004, by Steven Rosales.