By Nora Ramirez

For 58 years, the sounds of flying bullets and torpedo explosions have tormented Toby Fuentes.

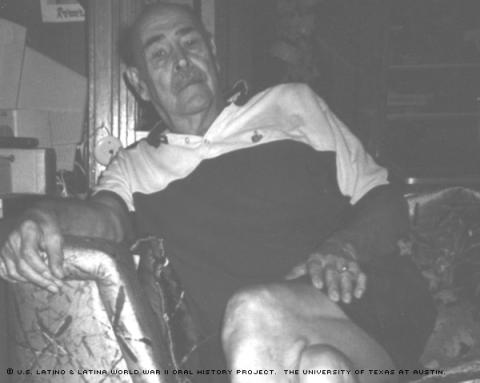

Sitting outside the porch of his house in a peaceful, almost rural area of East Austin, Fuentes recently recounted the sinking of his ship by Japanese torpedoes during World War II. His ship, the USS Chicago, was in a convoy of ships that was attacked by Japanese bombers in January 1943 during the Battle of Rennel Island in the Southwest Pacific. Although the Chicago survived an initial barrage, the crippled ship was attacked a second time a few days later and was sunk. Six officers and 56 enlisted men were killed. Nearby destroyers collected 1,049 survivors. Toby Fuentes was one of them.

"I thought the war was coming to an end in the water," Fuentes said, shrugging his shoulders.

Fuentes went from being an ordinary citizen to a man who served in WWII. He married Sandy Acosta, had four children and worked as an auto body repair man. And during the war, he survived the sinking of his ship.

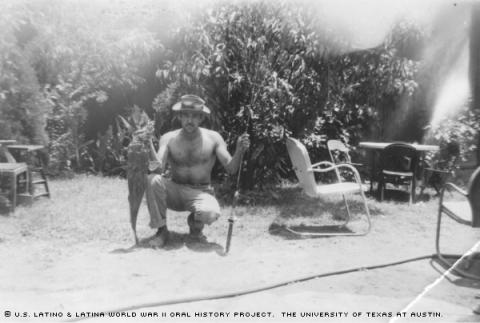

Fuentes remembers that his first stop after enlisting in the Navy was San Diego, Calif., where he completed boot camp. However, boot camp was not easy. Every morning everybody had to wake up early and "exercise, lot of training out there and also... row boats," Fuentes recalled. During his training he felt sure he had made the right decision to join the military.

"I wanted to go," he said. "Heck yeah -- that's what they taught for."

After boot camp in early 1942, he got his other orders to head to San Francisco where the USS Chicago would be waiting for him.

"I wanted to go to war and I wanted to go out there and fight," said Fuentes firmly.

He was allowed to come back to Austin for a couple a days and then go back to board his assigned ship. It was in Austin that he met the love of his life, Sandy Acosta, in Austin, a girl he had seen before but had not really gotten to know well.

Within three days of knowing her, he proposed marriage to Sandy. According to Fuentes the reply was "yeah, yeah, yeah!" With that reply Fuentes immediately followed the next steps.

"I did everything and I picked out everything out and the band and the whole nine yards," Fuentes exclaimed.

The war separated them for three years but even the distance and the time away were not strong enough reasons to break the love between them. They communicated with each other by letter and Fuentes wrote to her "at least once every two weeks."

As a kid growing up in Austin, Texas, he never imagined he would go to war. Fuentes attended school up to the 9th grade and had to quit because to help his parents. Even though his family did not have financial burdens, he was an only child and felt a strong responsibility since he was a boy. At the age of 15 he got his first job working part time at a library with his father. Three years later he went to work for a brick company.

"I helped my family and I made it," he said.

During this time the United States was going through difficult times. Serving in the war seemed like a good alternative.

Fuentes was interested in fighting for his country, he said. The United States was in a state of alert since the war efforts were going on and there was a propaganda campaign to encourage young men to enlist in the Army and in the Navy.

So at the age of 19, in early 1942, Fuentes enlisted in the Navy without notifying his parents. His mother was quite upset but nothing could be done to stop him. His parents had no alternative other than to support him and let him enlist even if that was against their will. Fuentes' father, John Fuentes, died of tuberculosis before Fuentes went to war. He said he was away at war for about three years and Sandy waited for him so they would live a normal life. For Fuentes it seemed like nothing changed after the war. After coming back from the war, Fuentes remembers his family and friends telling him "they were glad I was alive," he said with a smile.

The couple had four children: Martha, who became a teacher for the blind; Joanna, who became a housewife; Rolando, who became a hairstylist and owned a successful hair styling salon in Austin; and Cheryl, who worked for a local computer firm.

Fuentes' home was filled with dozens of photographs of his kids, grandkids, great grandkids - almost every inch of the wall was covered with framed photos.

His own father couldn't afford to send him to school, but he was proud to say that he did his best and gave his children a good education so they wouldn't go through the same hardships as he did.

He says his own hard work earned him respect. He did auto body repair for many years.

"I didn't have trouble getting a job; I worked for one company for 11 years ... and worked for a long time there," Fuentes said. "I was good - I'm not bragging-- I was good at it and they [other employees] appreciated my work. And whenever they got a raise, I got a raise. No porque era Mexicano: porque era Toby. (Not because I was Mexican, but because I was Toby.)"