By Kristina Radke

Despite the horrors he experienced during World War II, Tomas A. Hernandez has lived a full, happy life.

Hernandez was born on Dec. 29, 1925, in Temple, Texas, to Mexican parents.

"My father spoke broken English," he said; “my mother didn't speak English at all."

As a child, Hernandez went every year with his family to West Texas to pick cotton. His father worked on the Santa Fe Railroad and his mother stayed home to care for the children. Hernandez dropped out of school after completing fifth grade to continue to work. He secured a job with the railroad company, working alongside his father.

On their way back from picking cotton in Lubbock one year, Hernandez and his father stopped in San Antonio. They were walking down the street when they heard the news that Pearl Harbor was being bombed. "I didn't know what Pearl Harbor was," Hernandez said. "We thought it must be another country."

At the time, Hernandez was only 16, but he begged his parents to let him enlist in the service.

"My mom said, 'You're too young. You don't have to go,'" Hernandez recalled. After a year, they finally gave in and allowed him to enlist at the age of 17.

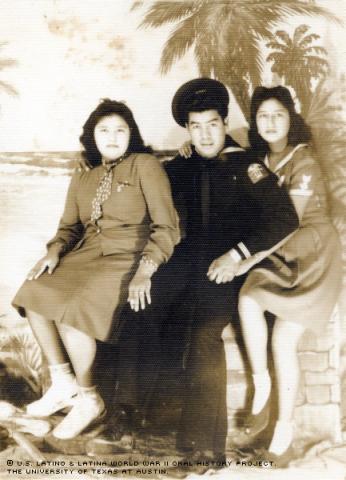

Hoping to become a Marine, Hernandez signed all of the requisite papers and went to the recruiting office in Lubbock, Texas. Finding the Marines’ office empty, but still determined to be in the service, he promptly walked down the hall to the next door and enlisted in the Navy instead.

Hernandez was sent to San Diego to complete boot camp, and then began amphibious training.

"I used to cry every night," he recalled, "thinking about my father, my mother, my sisters [who] I left. But I felt a little better because I was not the only one crying. Everyone was crying."

After training, Hernandez became an instructor for a year at the amphibious base in Coronado, Calif., across the bay from San Diego. He was then sent overseas.

Hernandez, then a seaman first class, remembered being aboard three separate ships: the USS Landing Ship Tank numbers 882, 660 and 666. LSTs carried smaller craft topside -- a tunnel-like hold full of 20 or so tanks, vehicles, guns, cargo or up to 1,000 assault-equipped Marines.

Although he never encountered any Latinos among the 175 crew members on the ships he was on, when his boat stopped in Okinawa, Japan, he was able to find some of his hometown friends because he knew on which ships they were stationed.

Hernandez's missions included picking up American troops from Iwo Jima after the island was taken and bringing them to Okinawa to invade. He made numerous trips back and forth, transporting the soldiers by boat.

His ship was preparing for the eventual invasion of Japan when he got word the Americans had dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, effectively ending the war.

After the war was over, Hernandez waited for permission to return home. Discharge was granted on a "points" system, in which men received points based on time enlisted, combat history and other criteria. Accumulating 75 points meant an enlistee could be sent home. On February 23, 1946, Seaman First Class Hernandez was discharged from Camp Wallace, in Galveston, Texas.

"It was a very different lifestyle coming back than it was before," he said. For one thing, the family dynamics had changed: His sisters had married while he was overseas and moved to Lansing, Mich.; one of his brothers also moved there from McAllen, Texas; and the family generally wasn’t as close as before.

"We were just growing [when I left]," Hernandez said. "When I came back, I was more alert to the things of life ... Things were more important -- bigger. ... When I got back, it was like someone opened a door to the world."

Hernandez had plans to return to school, but his father's new taxi cab business was struggling. So when his dad bought him a car, Hernandez remained at home and drove it as a taxicab. He attended a vocational school to learn how to work farm machinery, but ultimately remained with his father's company.

"The only thing I regret is that I never got an education," Hernandez said. "But the education I had and have was living through life -- where I've been, what I've done and how I've done it. It's been good to me ... [War] was my schooling in life. I was 100 percent a different person when I got out than when I went in."

When his dad died in 1950, Hernandez remained at home.

"I took care of my mother and my youngest sister and brother," he said.

By that time, Hernandez himself had a son, Agapito, who was the product of a 1951 marriage. The union didn’t last, however, and he divorced soon after the child was born. Hernandez remarried and had another son in 1960, Reymundo, but divorced once more. He never married again, but did have two more children, daughters Anna and Vanessa.

"Marriage was maybe not meant for me," said Hernandez, who despite having four children by different women, says they are all close and remains on good terms with his ex-wives.

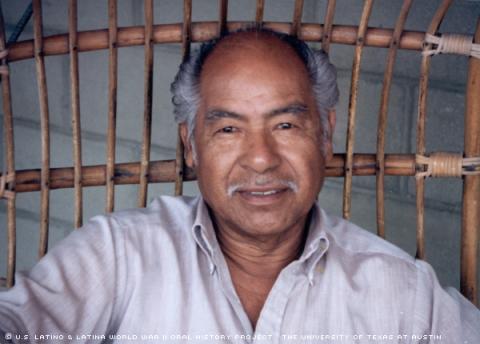

Although he doesn’t drink or smoke, Hernandez has undergone two major heart surgeries and intensive treatment for colon cancer that is now in remission. In spite of these health problems, he’s still able -- at 76 years old -- to play baseball with his grandson.

"Living by yourself, you have to move, be active," said Hernandez, who now lives in McAllen. "You have to be alert." Aside from baseball, he enjoys gardening, reading and, especially, dancing for keeping busy and fit.

"I don't have time to get sick," he said. "I don't have time to get lonely."

Although he has lived a fulfilling life, he concedes to not being completely happy.

"I still lack the main thing in life -- a companion," Hernandez said. "If I had the knowledge I do now -- respect of a woman's opinions -- I would never have divorced. When I come back home, there's no one there to say, 'How was your day?' I left four walls and I come back to four walls."

Besides this one unhappy fact, however, Hernandez says he’s satisfied.

"I can still walk around, move around, see all right," he said. "I like to travel a lot."

He also feels lucky.

"I had faith that I was coming back [from the war]," Hernandez said. "How? I don't know, but I came back."

After Hernandez’s first bypass surgery, his boss at the produce market where he’d been working told him, "I think you're on very good terms with the man upstairs," recalled Hernandez, who added, "I think it must be true.”

Mr. Hernandez was interviewed in McAllen, Texas, on April 6, 2002, by Andrea Shearer.