By Bettina Luis

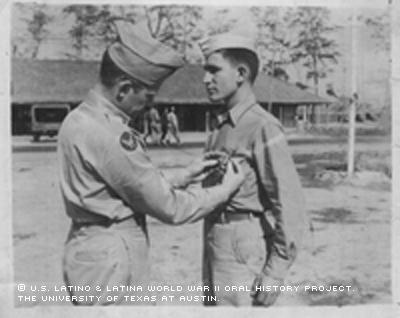

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas -- Standing at attention, his thumbs aligned with the seam of the trouser, his heels together at a 45-degree angle. Thomas Cantu Jr. looked straight ahead as he was awarded the Air Medal in 1943 for completing 150 combat flying hours.

Cantu served in the China-Burma-India theatre of World War II, carrying out 65 missions over the world's worst weather and highest mountains between January 1944 and September 1945. Stationed in India's Assam Valley, Cantu's squadron was part of the Air Transport Command, responsible for airlifting troops and supplies from India to China in order to keep the Allied forces in the fight.

There were different flight patterns that could be used: pilots could go through the mountains and battle the threat of Japanese fighters, or they could fly over the mountains where the Japanese planes could not follow. Most planes used in this theatre were slow unarmed transports - B-24s -- that had to "duck the enemy." Although this over-the-mountain route allowed them to elude the Japanese, it held perils of its own - the dangers of weather, as well as the technological limitations of their aircraft.

The planes had to reach altitudes of over 20,000 feet in order to maneuver around peaks such as Mount Everest. At these heights, the wings of their planes would ice over and the weather became the enemy. Thunderstorms and winds of 115 mph were common, as was ice and snow, turbulence and heavy rains. In planes without pressurization and minimal navigation tools, these trips over the Himalayas were anything but routine.

"It was nothing for a plane to just drop 500 feet," Cantu recalled in March, during an interview at his home in Corpus Christi. "All you could see was the snow and the mountains. It was scary... I've seen the pilot, many a times, sweat. I mean sweat cold. Being scared. Because many times they didn't think we were going to make it."

The intense flying conditions caused the loss of more than 1,000 U.S. airmen and 600 transport planes. The route became known as the "Aluminum Trail," for the bodies of the fallen aircraft that glittered in the sunlight.

But Thomas Cantu did make it, he lived to tell, and when asked to reflect on this time in his life Cantu also shared memories of his childhood in South Texas, war stories, and his life after his military service.

He was born in Robstown, Texas, 16 miles from Corpus Christi, on February 23, 1923. His father, Tomas Cantu, Sr. was self-employed and his mother, Caritina Zulica Cantu was a housewife. He had 3 brothers and 5 sisters, and was the 6th child. Cantu recounted stories about himself and his family.

He used to walk across railroad tracks, past the homes of Anglo families, to visit his uncle. Everyday, he walked by the same houses, and the occupants "would never say anything." One day, he and one of his brothers walked by speaking Spanish. Rocks were thrown at them. Cantu surmised that the neighbors had thought, before that day, that he was Anglo, until he spoke Spanish. From then on, Cantu had to take another route.

"It's just a thing that happened," Cantu said. "It was kind a rough, if you wanted to get ahead of the times, because there were so many obstacles you had to cross."

Expectations were not high for Mexican Americans. A teacher once said to him that he didn't need to be in school, but rather that he needed to get a job because he would never make it academically. His approach was to keep on trucking.

"You can't just sit in a corner and cry, or anything like that, you just have to go and do the best you can," he said.

Just prior to WWII, at a drive-in restaurant in Robstown, Texas, Cantu, his sister and a couple of friends, borrowed a convertible and went to eat and have a Coke. The server brought them water and a tray and she did not return to take their order. She came back much later and said, "Well I'm sorry but I can't serve you...You're Mexican." Shortly after that, Cantu went into the service.

Cantu didn't finish high school; instead, when the U.S. joined the war, he enrolled in a federal program funded by the Defense Department. These defense school programs trained young people so they would be prepared to contribute to the war effort. At seventeen, Cantu began learning the mechanics of his trade. Two years later, he joined the military. Cantu went from San Antonio to Biloxi, Mississippi for Basic Training. Then afterwards was sent to study with Trans World Airlines in Kansas City, Missouri. The defense school gave him the groundwork for what he would be doing in the military, "and then when you got there they would teach you the rest of it."

He moved from place to place for a long time, to remote sites such as Las Vegas, New Mexico. After acquiring the knowledge that he would need to serve as an aerial engineer, he was stationed in Reno, Nevada. In Reno, flying hours earned soldiers $75 more a month. However, anytime superior needed someone for details such as Kitchen Patrol, the sergeant would call on Cantu. So after four or five times, Cantu told the commanding officer, that he was there to work on planes and to go with the crew and get flying time, not just to work in the kitchen. The commanding officer questioned the sergeant and asked him why he always called out the private, and he said, "'His name is easy to pronounce, CAN-TOO.'"

After eight months in Reno, in November of 1943, Cantu volunteered for his tour overseas. He took a train from Nevada to Florida. On this journey, he stopped at a train station somewhere in the Midwest to eat. He walked into a restaurant in which blacks were not allowed to mix with white customers. As a Mexican American, Cantu was considered white, however, this place refused to serve black soldiers. Ironically, Cantu witnessed German prisoners eating in the restaurant under guard, but the black soldiers had to sit in the kitchen or find somewhere else to eat.

As Cantu recounted this scene, he said, "But things are not like that anymore. At the time I didn't pay too much attention to what happened. It was part of life, I guess. But now I can see that it was wrong."

The trip from Nevada to Florida was just the beginning for Cantu. He flew from Florida to Puerto Rico, then to Natal, Brazil. Because planes did not fly nonstop to South Africa, his plane landed in Acension, "a 10-blocks-long by 3-blocks-wide, piece of rock they called an island," to refuel there, he recalled. The plane would then continue on to South Africa, to Casablanca, before finally landing in the CBI.

Meanwhile, China was fighting against Japanese forces that held her north and eastern coastal strip. General Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Nationalist Army maintained the west and southwest; however, as the general fought the Japanese advancement, he also battled an internal enemy, Mao Tse-Tung, leader of the Communist revolution. The USSR was concerned that the Japanese would capture China and inhibit the communist revolution (which they supported). The US worried about their Chinese allies, and the British were concerned with Japanese victory-positioning aggressors near their territorial holdings. Thus, the Allies decided to maintain supplies to Chiang Kai-shek via the Burma Road, which ran through the mountains in India to northern Burma. When France fell to Germany in 1940, Japan pressured Britain to close the supply road. In 1941, Roosevelt agreed to the British request for a fleet of aircraft and pilots to maintain supplies to Chiang Kai-shek's Chinese army by flying a route that came to be known as "the Hump."

The Air Transport Command flew aerial supplies from 1942-45, and enabled the Allies to maintain a foothold in Asia, by tying down more than one million Japanese soldiers. Cantu described India by comparing the conditions to a popular television show. "MASH, exactly like that, with Hot Lips and all that, except we didn't have Hot Lips. We lived in tents, took showers like they did, it was just the same as that."

During these voyages over the Himalayas, Cantu, an aerial engineer, was responsible for things such as pre-flighting the engines, maintaining flight instruments, and making sure that the gas tanks were filled. Cantu ultimately received the Distinguished Flying Cross and was promoted to Corporal in 1944, for having completed 65 missions over "the Hump."

It was a very happy day when the war ended, as Cantu was one of the very first to come home on a point system based on how long soldiers had been overseas, awards received, and so on. When he returned home he went straight to that drive-in restaurant in Robstown, Texas, dressed in his uniform, hoping they would say they didn't serve Mexicans. But they didn't. They were very nice to him. Cantu's world changed after WWII.

After the war, Cantu returned to work in his father's meat packing company alongside his brothers. He received his G.E.D. and then with the aid of the GI Bill, enrolled in Del Mar College where he studied psychology and business courses.

"It was good to be back, back to work, back to school."

He had been engaged to be married when he went overseas, but things had not worked out.

"This girl used to write to me practically everyday. One day I get a letter saying that she was sorry, but that she had met, a pilot from Cuba, and she was going to get married. I was 5,000 miles away at the time, so what could I do. A funny thing happened that the letters would get mixed up, you know, so about 3-4 days later, I got another letter saying how much she loved me, but that one was supposed to come before. But anyhow, it happened for the best."

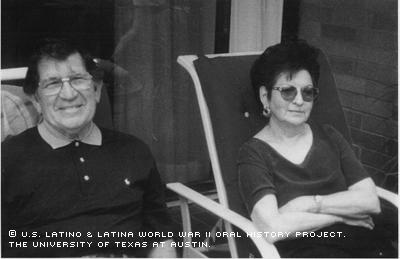

Claudia Ramirez, and Thomas Cantu were just friends who had met in high school. They dated, but during the war, she went her way, and he went his. Claudia served as a secretary in the Women's Air Corps for three years, and attained the rank of sergeant. The couple started dating again once they returned to South Texas, and was married in Corpus Christi, on February 2, 1947.

In this same year, the GI Forum was organized, and Cantu became one of the very first members. The GI Forum needed a hospital for the veterans because unlike other states, Texas did not give money to veterans. As it turned out, the organization started helping the labor group, the migrants, and it just continued to grow. As a founding member, Cantu used to be out until wee hours of the morning, looking for other veterans to join this new organization. He even went to Washington D.C. to place a wreath on the grave of a Mexican American soldier from Three Rivers who was not allowed to be buried in his local cemetery due to racial issues.

His family grew, as the couple's first daughter Cindy was born in January of 1948, followed by their daughter Cathy in January of 1949.

In 1951, the Cantu brothers decided to move on, and Cantu bought the business from his father. But when things got bad 7 years later, he was forced to sell the Cantu Packing Company. His daughter Christine was born in February of 1954, and in order to support himself and his family, Cantu moved them to McAllen, Texas. He continued working in the packing business as a salesman, and a year after his son Thomas was born in May of 1960, the family returned to Corpus Christi. Cantu sold cars for a year or so, and then became a manager for Lew Williams Chevrolet. Cantu worked there for 12 years, and then went into business for himself. He worked and saved as much money as he could, but it was tough because he had three children attending school. However, Cantu did manage to save enough to open his own business. He started small, worked hard, and founded Tom Cantu Motors, Inc in 1974.

"When you're in business for yourself, it's grinding," Cantu mentioned as he spoke about his car dealership, "It's gone up and down, and I just sold the business again. I can't retire, because I've always worked. So I'm going to go back to selling cars for a local dealership. Want to buy a car?"

Cantu advised younger generations to take advantage of the opportunities that are set before them.

When asked what difference WWII made in his life, Cantu recited a quote from President Kennedy and said, "'It's not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country. So I figure that there are a lot of Mexican Americans that have done our jobs and some have not gotten credit for it. It's a good feeling to leave a mark and say, I've done my job."

In doing his job, the war would leave Cantu with many memories.

Cantu was saddened by a memory of a fellow soldier who used to sleep next to him in the barracks. One morning the chiefs came in and rolled his bed, because he had been killed the night before.

"He had always spoken about what he was going to do when he got back," Cantu recalled. "Somebody had to do the job, and some where not as lucky as us."