By Stephanie De Luna

At around 1 a.m. on Jan. 10, 1969, gunner Uriel “Ben” Bañuelos and other soldiers were roused from their sleep at Fire Support Base Pershing, 40-50 miles northwest of Saigon.

Bañuelos and the other men were in an underground bunker. He remembered it was a hot night. Bañuelos got up and put on his helmet and his jacket. He later said they probably saved his life.

A mortar round struck inside the gun parapet, recalled Bertram S. Allen Jr., a friend of Bañuelos. In a letter years later, Allen said “the shrapnel from the exploding mortar round sprayed throughout the parapet, hitting all of us who were firing that night.”

The commanding officer, 1st Lt. John Farley, lost a leg. Bañuelos was struck on the back and was knocked out.

“The only thing that I remember is that I was curled up on the ground, and I remember shaking, and I remember feeling like electricity was running all over my body,” Bañuelos said. “I thought for a while, ‘Man, I’m going to die.’ ”

Father Donato P. Silveri, a Catholic chaplain, and Allen carried Bañuelos to the aid station “near the chopper pad across the fire support base from the artillery battery.”

“The medic then began cutting your flak jacket off to give him access to your wounds,” Allen recalled. “I could see huge craters in your back and shoulders, bleeding some but oozing more. I started graying out as if I was going to pass out from what I was seeing,” he said.

Allen remembered that Bañuelos asked him how he was doing.

“That struck me as unreal,” Allen wrote. “Here I was, only hit a bit, and you, who were really messed up, were asking how I was.”

Bañuelos was sent to the first of three hospitals. His injuries included a collapsed lung.

More than 15 scars on his back, legs and arms still remind him of the day that changed his life. He spent time in hospitals in Vietnam, Japan and Colorado, from Jan. 10, 1969 to April 17, 1969, and then went home.

Bañuelos received an early honorable discharge after his hospitalization. He said he hadn’t been issued a DD214 form, a document proving his military service, when he was discharged. He recalled that “the discharge doctor told me I wasn’t qualified to receive disability [compensation] because my injuries weren’t severe enough.”

He was awarded a Purple Heart, a National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal and a Vietnam Campaign Medal, as well as an Army Commendation Medal for “unrelenting loyalty, initiative and perseverance.”

Bañuelos was born in Valparaiso, Zacatecas, Mexico, and that fact, he said, frustrated his attempts later in life to secure rehabilitation and federal employment.

Bañuelos arrived in Vietnam in March of 1968, but he didn’t know that fighting for his country and getting severely wounded were only half of the battles to come.

“Here I went to Vietnam. I almost got killed over there. I came back home, and I’m asked for my papers because I’m Mexican,” said Bañuelos. “I served, came out, and I wasn’t a citizen anymore.”

Bañuelos said he was denied treatment at the Department of Veterans Affairs several times because he was told that the hospitals had no record of his Army service. Several hospitals told him that his records had been destroyed in a fire. He said he later found out that was a lie.

“I have to be honest: I hate that part of my life, and some of it that is still going on with me. I couldn’t deal with the reality,” said Bañuelos.

Bañuelos’ father, Manuel Garcia Bañuelos, was born in Morenci, Ariz. As a child he moved to Mexico with his mother and lived there for about 15 years.

His father later met and married Cecilia Nava. The couple had seven children in Mexico, including Bañuelos. His father decided to move the family back to Arizona in 1954, when Bañuelos was eight, and worked as a miner at the Esperanza Copper Mine in Miami, Ariz. The family’s last child was born in the United States.

Bañuelos attended school in Tempe, Ariz., where he finished one year at Tempe High School and left in 1963. “I had to quit to help support the family,” said Bañuelos. He worked as a butcher.

He was soon drafted into the Army. When he reported for duty at Fort Bliss, Texas, he learned he was shipping out right away. “They gave us about two hours to pack our clothing and say ‘bye’ to our relatives,” he said. He was first assigned to the 7th Battalion, 11th Artillery Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, and later transferred to the division’s 1st Battalion, 8th Artillery Regiment. He arrived in Vietnam in March 1968.

Letters he provided to the Voces Oral History Project illustrated the close friendships he made with fellow soldiers. One wrote about how much he appreciated Bañuelos sharing his experience with new gunners.

“The gunner did not have to take his time to tell us this.” Bañuelos said. “In fact, most of those who had been in country for some time did not take the energy to tell us new guys anything. We just got it on our own.”

After the war, his search for job security was elusive. Bañuelos did odd jobs, including working for heating and cooling companies, until he found a promising job at the post office. But when he went in for his first day of work, he was told the post office couldn’t hire him.

“She said I wasn’t a citizen,” Bañuelos said, remembering the woman he spoke to. “All this time I thought I was a citizen since I had been to the war.”

Refusing to give up, Bañuelos decided to stop by the immigration office. The employee at the office told him that he couldn’t become a citizen because when he was a teenager he was caught drunk and sent to juvenile detention, and that affected his record.

“Why don’t you look at the good things I’ve done for this country? Why don’t you check my military records?” he asked them. Bañuelos threatened to write a letter to the U.S. Congress. But he didn’t carry out his threat.

Nevertheless, few weeks later, the immigration office called Bañuelos to give him a date for his swearing-in ceremony. He was sworn in as a citizen on July 21, 1972. He returned to the post office to begin his job, but they had already hired someone else.

“I felt like I was used like a rag and thrown away. I had to deal with all of the discrimination,” Bañuelos said. “I wanted to escape reality. I wanted to feel good about myself.”

Finding himself at a dead end, Bañuelos turned to alcohol and drugs.

“Being a Vietnam veteran, I suffered a lot of depression and anxiety and anger,” he said.

On Aug. 28, 1972, Bañuelos married Margarita Cuevas, a native of Mexico, in Phoenix.

Margarita had one daughter by a previous marriage, and the couple eventually had two sons.

Finally, in October 1972, he was hired at the post office. In 1987, Bañuelos got sober and has remained so since then.

“My wife went through all this; my kids went through all this. I’m very thankful for my wife and that she went through all this with me.”

Bañuelos visited specialists at the VA to ease his pain. He’s been through many sessions of therapy and has received several in-hospital PTSD treatments, which are about 90 days each.

“When you go back to those days in combat and you see all those young kids dying around you, some burned, some bleeding to death, some with body parts scattered. … When you hear what they’re saying just before they die. …” he said.

He is haunted by the futility of the war. “For all those moms and dads and sisters and brothers that lost a family member, I keep asking myself ‘Why? Why did they have to die?’

“There’s never a good answer,” he said. “I’ve been fighting this … since I was wounded in Vietnam,” he said.

Despite those unanswered questions, and despite the fact that he was at one point turned away by the country he considered home, Bañuelos remains proud of his service in Vietnam.

“I had a chance to go back to Mexico. It wasn’t in my blood to run, like a lot of Americans did,” he said. “The only thing that I have ever hoped was for people to look at you for what you are, not the way you look, not to be so fast to judge without knowing where they’ve been or what they’ve done,” he said.

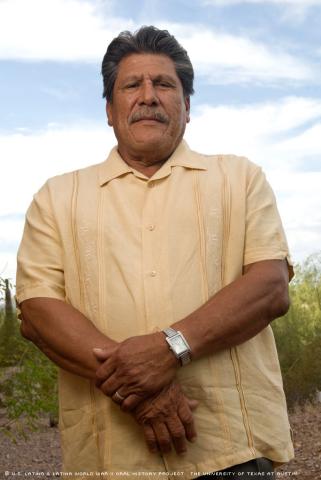

Mr. Bañuelos was interviewed in Tempe, Ariz., on Aug. 16, 2010, by Samantha Salazar.