By Rachel Hill

Voter participation was always a priority for former gym teacher Velia Sanchez-Ruiz, who grew up under segregation in Texas. Sanchez-Ruiz, who was 71 at the time of her interview, recalled what life was like as she grew up in of Lockhart, Texas, 30 miles southeast of Austin, during that period. She was born in 1942, one of seven children born to Cruz Garcia-Sanchez and Adela Mayo-Sanchez, a civil servant that worked at Bergstrom Air Force Base and a homemaker. They lived on the Mexican and African-American side of the city.

"We were fighting just to be seen as human beings here in Central Texas, just because it was so segregated and bigoted," Sanchez-Ruiz said.

Her first real experiences with discrimination occurred in and around the "barrio."

Sanchez-Ruiz attended La Navarro School until schools were integrated in her fourth grade year. Even though the schools were integrated, the classrooms were still segregated.

"White kids were on one side, Mexican kids were on the other in a classroom," Sanchez-Ruiz said.

The cultural differences made it difficult for her and her friends to make the transition into the White school, which caused Sanchez-Ruiz to often feel defensive in situations involving her and the White children.

Sanchez-Ruiz lamented going home after school every day "disheveled" because she was "ready to fight," and constantly felt humiliated.

Though the transition to high school was not any less of an issue racially, Sanchez-Ruiz, along with the 18 other Mexican-Americans in her graduating class learned of an opportunity to receive financial aid for college from Dr. A.L. Weinberger, civics and geography teacher, who was also a school counselor. It allowed some of the Latino students to further their education after graduation and escape the small town.

Sanchez said that she had jumped at the opportunity to attend college and get as far away from Lockhart as possible. She set her sights on Texas Woman's University, in Denton, 250 miles north of Lockhart. The university had a well-known dance program - and Ruiz wanted to be a dancer. But she found that she was unprepared. The other girls, who were Anglos, had been taking ballet lessons since they were little. The only dance that Sanchez-Ruiz had learned in Lockhart was the "Mexican Hat Dance."

She switched to health and physical education and received training that was more involved than just sports. She learned discipline, kinesiology and nutrition. It was a solid education that would be sought-after by school districts that knew the value of a degree in health and physical education from Texas Women's University. Her university education and living in Denton broadened her horizons.

Although the university began admitting men in limited programs in 1972, when she was there in the 1960s, it was an all-female institution. She learned that other Mexican-American students had experiences far different than her own. Some of the other girls were from border towns, such as Laredo. In those cities, she said, Mexican-Americans did not experience the racial discrimination of towns like Lockhart. She had assumed, she added, that all Mexicans felt like she did, no matter where they were from.

In Lockhart, though, Mexican Americans were, she said, "just fighting for the right to be seen as a human being, not as a second-class citizen because your skin was a little bit different."

It was also in Denton that she witnessed her first civil rights demonstration in 1964. It was at the lunch counter of a restaurant called The Pig Stand. When two White men and a black man sat down at the counter to be served, they were quickly escorted by the restaurant's managers out into a crowd of students picketing the establishment.

"I was flabbergasted," said Sanchez-Ruiz, an ardent supporter of integration.

Sanchez-Ruiz also had become aware of the importance of voting as a child when she watched her father vote.

"My father was a strong believer in [President Franklin D.] Roosevelt and voted Democrat," Sanchez-Ruiz said. "In my world, [parents] didn't really talk about [voting] very much."

But there was an underlying understanding that voting was important. When she was a child, her family attended neighborhood Poll Tax Dances, raising the $1.75 tax so that people could pay the tax in order to vote, a practice that would later be banned as unconstitutional. She attended her first such dance at age 13.

"It was a family event. We knew our people loved to sing and dance," Sanchez-Ruiz said. "The girls would wear poodle skirts; Saturday nights were our dance nights."

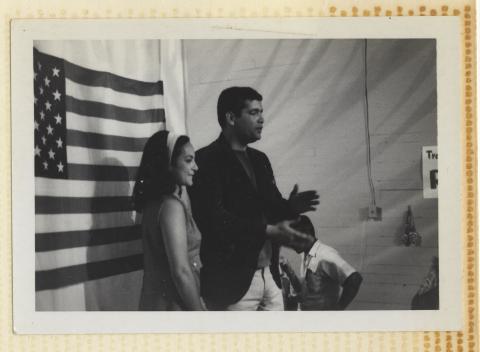

Her interest in politics also stemmed from the election of President John F. Kennedy in 1960. After she married Santo J. Ruiz, in 1963 and graduated from Texas Women's in 1964, she began to participate in demonstrations with her husband and their friends.

"It was a very exciting time; we protested, and I loved it," Sanchez-Ruiz said. "'The squeaky wheel is the one that's going to get listened to. So we squeaked a lot."

When the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, she was fully aware of its importance.

Although she took part in a variety of demonstrations, including protests favoring passage of the Voting Rights Act, Sanchez-Ruiz said the impact of the Voting Rights Act was somewhat lost among the uninformed Latinos.

"My expectations were for people to really get excited about voting," Sanchez-Ruiz said. "But the attitude for a lot of people was, 'It doesn't really matter -- my vote doesn't count.' "

Sanchez-Ruiz and her union organizer husband also protested on behalf of the workers in the1968-1970 Economy Furniture strike in Austin, Texas. She recalled how the demonstrators marched down Congress Street while Texas Rangers pointed rifles at them from the high floors of buildings.

Ruiz was an organizer of the strike that followed the refusal by Austin's Economy Furniture Co. officials to recognize their workers 252-83 vote in favor of union representation. At the time, 90 percent of the company's 400 workers were Mexican-Americans, according to the Texas Historical Association account. Because of that ethnic make-up, the collective bargaining effort had strong civil rights implications.

"I was pregnant," Sanchez-Ruiz recalled. "We had all of our kids with us. [We] took our Pampers and went wherever the guys were demonstrating." The couple later divorced.

She said that Ruiz had been trained the founder of modern community organizing, Saul Alinsky, in the mid-'60s. In addition to working as a union leader, Ruiz successfully led efforts to remove a junkyard from his neighborhood and later lobbied for the opening of the Palm and Sanchez elementary schools in Austin. In 1969, he became the first Chicano to run for the Austin City Council. Sanchez-Ruiz campaigned for him, offering rides to voting centers and free tacos. He lost the election.

"It wasn't something that I was watching on television," she recalled. "I lived it."

Sanchez-Ruiz worked as a physical education teacher for 33 years. Her first job was at Harlandale Middle School, in San Antonio. Later, she taught at the Becker and Linder elementary schools, in Austin.

Even after retiring from teaching 13 years prior to this interview, she continued to work on increasing voter participation.

"My generation opened doors," she said. "The voting and the activism still continue, and the voting is where we can make a difference."

One ongoing challenge, Sanchez-Ruiz said, was that a large segment of the Mexican-American population lacks faith in elected politicians, making it hard to rally people to vote.

"I still think it's a problem getting people to recognize the Voting Rights Act giving us the right that we had been fighting for, for a very long time," Sanchez-Ruiz said. "We have to continue improving and getting better at everything we do. Life is not static; it's dynamic. We have to keep moving -- we have to keep changing."

"Economics has a lot to do with what's going on in your life," she said. "If you don't have enough to eat, you're not going to be thinking about politics."

Ms. Sanchez-Ruiz was interviewed by Rachel Hill in Austin, Texas, on Oct. 29, 2013.