By Mario Barrera

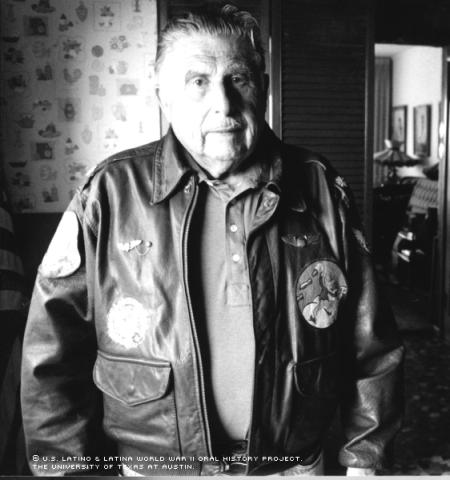

William Carrillo knew he wanted to go into the Army Air Corps when he enlisted in 1942, but there was a problem: He didn’t have the required college degree for the Air Corps Cadet program. So on the application form the resourceful Carrillo entered "College of Hard Knox." By the time anybody noticed that Hard Knox was not an accredited institution, Carrillo was on his way to the cadet program. If he’d known how many hard knocks were in store for him in Europe, he might have had second thoughts.

After pilot training at various U.S. locations, Lieutenant Carrillo flew a B-17 bomber to England, where he was assigned to the 100th Bomb Group of the 3rd Division, 8th Air Force. While stationed at a British air base that was sometimes bombed by the Luftwaffe (German Air Force), Carrillo flew 24 and a half missions, initially over France and then into Germany, usually encountering heavy anti-aircraft fire and attacks by German fighters.

On his 55th mission, May 24, 1944, he was shot down over Berlin. Carrillo still doesn't know how many of his 10-member crew survived that day, but he does know his co-pilot and radio operator were killed by anti-aircraft fire. After bailing out, Carrillo found himself crashing through the slate roof of a Berlin house, ending up with his legs in the attic and the rest of him sticking out of the roof. He was pulled down into the house by an elderly man, a member of the Volkssturm (People's Army), a kind of home guard consisting of those too old or too infirm for the regular army.

The man, who spoke no English, kept poking Carrillo with the bayonet of an old rifle until a gas cartridge went off on his Mae West life preserver, suddenly inflating and startling them both. At that point, Carrillo was sure he was going to die.

Instead, the Volkssturmer turned him over to two members of the Gestapo, who proceeded to interrogate him for the next two weeks, hoping to learn something about the impending invasion of Europe. After beatings and other atrocious tortures that left Carrillo with a set of broken toes and other injuries, the Gestapo concluded they would get nothing out of him and turned him over to the Luftwaffe.

From then until the end of the war, Carrillo was kept in a Luftwaffe-run prisoner of war camp in Poland and subjected to extended, but less brutal, questioning. His chief interrogator turned out to be the notorious "Gold Tooth Major," an American of German descent who had decided that Germany was going to win the war and had gone to join the "Master Race." During this time, Carrillo was flabbergasted to learn the Germans already knew almost as much about him as he knew about himself. The Gold Tooth Major produced a large thick notebook corresponding to the 100th Bomb group, turned to the William Carrillo section and read out Carrillo's birthdate and birthplace, the names of his parents and siblings, the date of his enlistment, the location of his barracks in England and numerous other facts about him, all accurate. They had information on him up to a few days before he was shot down.

While in captivity, Carrillo and other captured airmen were offered the choice of joining the Luftwaffe in order to fight the Russians, an option he "respectfully" declined, despite being offered inducements that included the promise of free sex with attractive young women.

In 1945, as the Soviet army advanced through Poland, Carrillo and his fellow prisoners were moved to another prisoner of war camp, close to Munich, Germany. There, they were liberated by Patton's Third Army, with General George S. Patton personally driving the tank that smashed through the gates of the camp. Patton returned several times to talk to the prisoners, and to curse General Eisenhower for allowing other military units to enter Berlin before Patton. According to Carrillo's recollections, the only way Ike was able to keep Patton from disregarding that order was to restrict gasoline supplies to Patton's tanks.

Although Carrillo had been promoted to the rank of captain while in captivity, he never received the Army wages that were accumulating for him while he was held prisoner, supposedly because of lost paperwork.

Upon his return to California, Carrillo went back to work for his former employer, MJB Coffee of San Francisco. Prior to the war, he’d worked at MJB as a janitor, since, according to Carrillo, Mexicans were considered too dumb for other jobs. When it was found out he’d been an officer, however, he was moved to a management position, eventually serving as general manager until his retirement in 1995.

Carrillo married his wife Veronica in 1948, and the couple had five children. Today they live in Daly City, south of San Francisco, where they keep busy with various projects and their 12 grandchildren.

Mr. Carrillo was married in Daly City, California, on June 7, 2001, by Mario Barrera.