By Kassandra Balli

“I know I pulled him back to the safe area, but I don’t remember how I did it," said Vietnam veteran Tony Alvarado, recalling the day he rescued a fallen comrade during the battles for Hills 861 and 881.

When snipers attacked Alvarado’s Marine platoon, part of the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines, only eight out of 30 men survived.

Alvarado was born on June 13, 1946, in Atascosa, Texas, to Filemon Alvarado and Dominga Flores Alvarado. His father also was born in Atascosa, and his mother was born in Devine, Texas. Alvarado was one of seven children. He had three brothers and three sisters. They grew up in a farming community.

He and his brothers helped out by working on the 500-acre farm and ranch that their father leased just outside Lytle, Texas. His mother was a housewife. She raised turkeys on the farm.

Alvarado recalled that the school bus picked up children outside the gate of their ranch and took them to the nearest school, about 11 miles away.

Alvarado said he never experienced any discrimination in school or in the community. Anglos and Hispanics got along, he remembered. Race was never discussed in his household because it was never an issue, he said. Alvarado said his town could have been a role model for other towns that struggled with race issues.

His parents always stressed the importance of education. His father did not know how to read or write. He did not have any schooling and signed the letter X for his name until he learned to write his name at age 47. His mother was educated, and she could write in English and Spanish.

Alvarado learned English when he started elementary school at Somerset Catholic School. Before that, he only spoke Spanish. He remembered that his mother regularly listened to Spanish radio stations, and the Alvarado family spoke Spanish at home.

When Alvarado and his siblings returned from school their parents made sure they finished all their homework before putting them to work the fields. They planted watermelons, peanuts, and corn, picked cotton and worked on machinery.

Working on the farm had a big impact on Alvarado, he said. The work taught him discipline, how to safely work with machinery, and how to make important decisions. He felt these skills helped him adapt to military life quicker than those who had never worked before.

Alvarado played football when he was in high school, and he and his brothers were on the same team. But most of their free time was spent helping on the farm.

Before the end of his senior year in 1965, Alvarado received his draft letter. He was called into Army service a few months after graduation on Jan. 6, 1966.

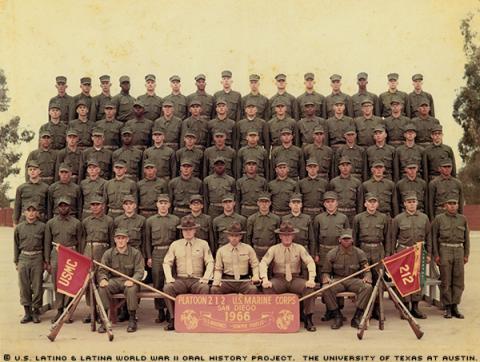

When Alvarado showed up for duty, he was told that the military needed some of the Army draftees to join the Marines instead. Alvarado nudged the guy standing in line next to him, and they joined the Marines together. The man’s name was De Bosque, Alvarado recalled, and he and Alvarado became good friends. They went through boot camp in San Diego, Calif., and combat training together.

After training ended in June 1966, Alvarado was sent home for a month before leaving for Vietnam in July.

He never knew how his family felt about him being drafted into the military because it was never discussed. He kept in touch with his family by writing letters. His mother wrote him a letter every day during the two years he served, and Alvarado remembered how those letters comforted him.

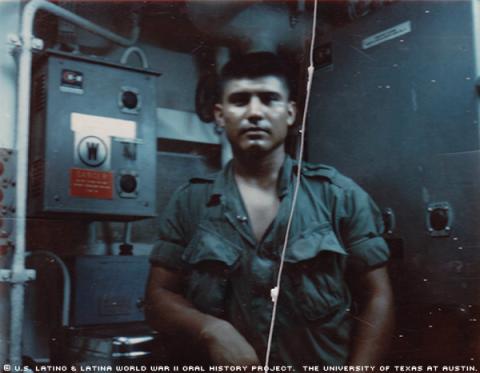

On March 25, 1967, the Marines in Alvarado’s company were on a cleanup operation, about halfway through an open field in a straight-line formation, when the enemy opened fire on them. There was nowhere to hide, and the Marines hit the ground. Their sergeant told them to get up and move forward.

As they waited for air support to arrive, the enemy fired a mortar round that exploded about 10 meters away from them. Alvarado suffered a leg wound. A machine gunner’s eyes hung out of his head.

He remembered that shrapnel was embedded in the body of fellow Marine Michael J. Bosch. “I thought he was dead,” Alvarado wrote later. Years later, Alvarado searched a website listing the names of Marines killed or wounded in action, and there he learned that Bosch had survived.

Some Marines died during this mission, Alvarado said. He and six to eight other Marines were wounded. Alvarado spent 13 to 20 days in a hospital recovering from his injuries before returning to his company.

The next major combat actions Alvarado saw were the battles for Hill 861 and 881 in April and May 1967. He said that as the Marines walked up one hill, the enemy fired down at them from the top.

Alvarado pulled a friend, Roland Lee Lyvere, into the safe area. The friend died, and Alvarado remembered how deeply that death affected him.

Alvarado said that there have been books and stories written about the battles, but the books have it wrong. For example, he said, one book said his friend was shot in the head and died instantly, when in fact he was shot through the shoulder and was struggling to hold onto life.

Alvarado said the military told the man’s mother that her son was killed by hostile fire, but she was not given any details. Alvarado decided he would write a letter to the mother of that Marine when he returned to the base camp, explaining in detail how her son died. She wrote back to him, thanking him and inviting him to visit her when he returned from Vietnam.

His platoon received replacement Marines and then continued its search-and-destroy missions. During Alvarado's last mission, he was told he was going home when the mission was over.

When Alvarado returned to the United States, he finished the last three months of his military duty as a military policeman at Camp Pendleton, Calif. He ended his term of service on Jan. 6, 1968, and was discharged as a corporal. His decorations and medals included the National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal and Purple Heart.

After the war, Alvarado returned to Atascosa and worked in civil service. He married in 1970 and had six children.

(Mr. Alvarado was interviewed in Castroville, Texas, on Nov. 6, 2010, by Kassandra Balli.)