By Lauren Harrity, California State University, Fullerton

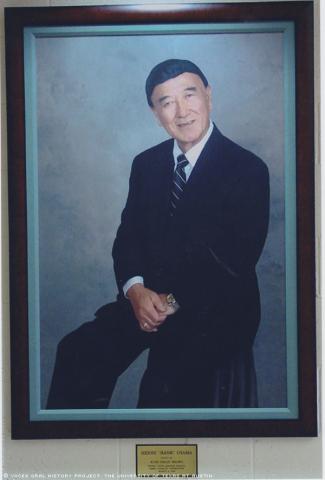

After growing up in a Spanish-speaking Japanese-American family in Tucson, Arizona, Henry "Hank" Oyama went on to be a tireless supporter of bilingual education for American children.

Oyama always felt more Hispanic than Japanese-American. His mother, Mary Matsushima, was raised in Mexico and spoke primarily Spanish; his father, Henry Heihachiro Oyama, died shortly before he was born. His neighborhood friends were mostly Hispanic.

"Tucson was like a small Mexican town at this time," Oyama said.

Growing up during the Depression in a single-parent household meant that money was tight, but his mother always had an upbeat demeanor in front of him and his sister Rosalie. She always told them, "There is nothing bad that happens but for some good reason."

"I was a very happy child," Oyama said. "My mother really determined the direction my life would go."

Although Oyama and many in his community spoke only Spanish, they were still required to speak only English in school. In elementary school, Oyama began to learn English.

"I learned more English than a lot of English-speaking students in other parts of the country because they [the teachers] paid attention to all the details and the grammar," Oyama said.

When Oyama was in eighth grade, many Japanese-Americans were being sent to internment camps because of the fear caused by the Pearl Harbor attack. Oyama, his mother and sister Rosalie were among the 120,000 Japanese-Americans sent to internment camps. He was just 15 years old at the time.

"We didn't know what would happen or if we would be coming back from the internment camp," Oyama said.

Despite the family's fears, his mother maintained her characteristic upbeat attitude and Oyama soon adjusted to his new surroundings. He spent two years at the camp located near Poston, Arizona (about 173 miles west of Phoenix).

"During my time there I was quite happy," Oyama said. "Some people didn't have it all that bad, and we weren't there for long."

During his time in the internment camp, Oyama became interested in joining the military, as he loved the way the soldiers were depicted in the movies and songs. Despite his eagerness, the law would not allow only sons to enlist without their parents' approval, and his mother told him he would have to wait until he was 18 to enlist. He didn't have to wait long to get his wish.

"I didn't even have time to enlist," Oyama said with a laugh. "As soon as I turned 18 I was drafted."

Oyama was sent to infantry basic training and then Military Intelligence Service Language School with orders to be an interpreter in the South Pacific. When Oyama explained that he did not speak any Japanese and had actually grown up speaking Spanish, he was reassigned to counterintelligence. He was sent to Panama as an undercover agent with orders to protect the Canal Zone.

"I was very fortunate in the arrangements I got," Oyama said. "There was some danger, but for the most part it is humdrum activity and a lot of surveillance, eavesdropping and protecting high-ranking officers."

Although there was little action at his post, Oyama said he was glad he was assigned to intelligence work because it meant he would not have to be in combat.

When his service was up in 1947, Oyama used the GI Bill to enroll at the University of Arizona at Tucson, where he earned bachelor's and master's degrees in education.

Oyama began his teaching career at Pueblo High School in Tucson, where he taught history. There, he met and fell in love with the woman who would go on to be his first wife, Mary Anne Jordan. When they tried to get married, however, they were denied their license as there was a state law forbidding interracial marriage, and Jordan was white. Outraged at the injustice, Oyama began what would become a lifelong struggle for the rights of all people, no matter what their race or ethnic origin.

Oyama and Jordan hired lawyers to fight the law, first at the local level and then at the state level. Late in 1959, the law was declared unconstitutional. The couple garnered national attention for the achievement and were married soon after the law was repealed. The U.S. Supreme Court in 1967 declared a similar law in Virginia unconstitutional, making interracial marriages legal throughout the United States.

His quest for change did not end with the marriage law. While teaching at Pueblo High, Oyama and some of his colleagues began teaching honors-level courses designed to teach Spanish speakers how to read and write in the language.

"What we want is to enrich our community and our country," said Oyama. "We need Americans in all walks of life who can communicate in other languages."

Soon after establishing the programs at Pueblo, Oyama and his colleagues implemented them at nearby Pima Community College. He, along with six of his colleagues, later wrote a report titled The Invisible Minority, about the need for change in the education of Hispanics throughout the country.

According to a story published in Tucson.com, the website of the Arizona Daily Star, in 1966 the National Education Association held a symposium with congressional delegates and senators where Oyama and his colleagues discussed their findings.

Sen. Ralph Yarborough of Texas was so moved by Oyama's findings that he introduced the first bilingual education law, making Tucson the birthplace of modern federally sponsored bilingual education. Thanks to the legislation, schools across the nation now have programs teaching Spanish and other languages.

"What we want are strong Americans who can speak both languages with equal facility in the military, government, business and the private sector. We want them to be proud of their culture," Oyama said.

After leaving Pueblo High in 1970, Oyama continued his teaching career at Pima Community College, where he was appointed director of bilingual and international studies. He went on to become an associate dean of the program, and later vice president of the college.

The changes that Oyama began brought him national attention, and he won numerous awards for his work. He was named Man of the Year by the Tucson Chamber of Commerce and one of the 100 Most Interesting People in the history of Tucson by the Arizona Daily Star. He also received an honorary doctorate from his alma mater, the University of Arizona.

Despite his many accolades, Oyama remained humble.

"It was really the work of my colleagues that pushed me into positions of visibility, and they were really the ones who were the contributors," he said.

Oyama retired from his career in education in the early '90s but did not stop his quest to make people feel proud of their heritage and to promote bilingual education. He started an endowment that provides scholarships to students looking to improve their Spanish through courses at Pima College. His hope for future generations was for them to give back to their community.

Through his work in promoting bilingual education, Oyama sought to bring people together and show how important it is to have different ethnic backgrounds recognized and respected in all areas of the community.

"We have Americans with different ethnic backgrounds, but they are just as American as everyone else," Oyama said emphatically. "Rather than divide us, we should bring people together."

Mr. Oyama was interviewed by Taylor Peterson in Tucson, Arizona, on Aug. 17, 2010.

Disclaimer: The Voces Oral History Project attempts to secure review of all written stories from interview subjects or family members. However, we were unable to secure that review for this story. We will accept corrections from the interview subject or designated family members - contact voces@utexas.edu.