By Laura Carroll

Quirino Longoria recalls joining the long Navy tradition of being initiated – or, according to some, hazed – a “Shellback” upon his virgin crossing of the Equator in 1945. New seamen are designated “Polliwogs” until they complete the Equator crossing ceremony, at which time they become hardened “Shellbacks.”

Sailing from Fremantle, Australia, Longoria and his crewmates were responsible during that voyage for the transport of personnel to India. The Indian Ocean being a “hot spot” of Japanese submarine activity, Longoria’s ship, the U.S.S. General E.T. Collins, accompanied by a British destroyer, “zigzagged” its way to Calcutta carrying more than 600 women, including Army nurses and Red Cross workers, Longoria recalls.

The ship’s next assignment started out being the return of two- and three-year war veterans to California. This task was interrupted by the end of World War II, however, as the war-weary troops were re-directed to Japan.

“We took ‘em to Japan to invade Japan. They were mad, of course, because they wanted to come home, but they had to go and do their job in Japan,” Longoria said.

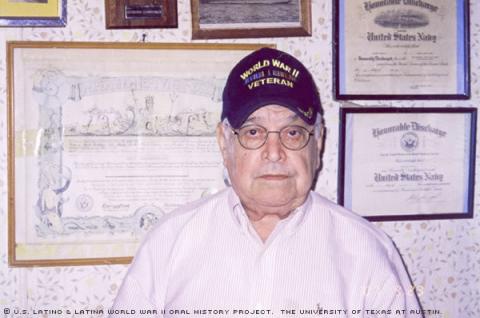

Born Jan. 29, 1927, in Mission, Texas, Longoria joined the Navy at the age of 17. The middle child of five, it was at the insistence of his older brother, Juan, or “Johnny,” that their parents, Procopio and Sofia, give permission for Quirino to join the Navy before he could be drafted into the Army at the age of 18.

“The reason I went in the Navy is because my brother was in the Army and he was going through hell in the Aleutian Islands fighting the Japanese. They had hand-to-hand combat and all that,” said Longoria, who recalls sharing a letter from Johnny with his parents to convince them to allow him to enlist.

Longoria considers his Navy service to have been a positive experience and source of pride, one that opened his eyes to the wider world outside of the Rio Grande Valley and afforded him opportunities he wouldn’t have had otherwise. With a scarcity of Mexican-Americans aboard his ship, he was befriended by Anglos from the North. Raised to speak both Spanish and English, he didn’t realize he had deficiencies in his education. Though he vividly recalls speaking Spanish in school was punishable by spankings, it was his Navy crewmates who made him aware of how the rest of the country spoke and pronounced certain sounds. Longoria remembered realizing there were things “not right in the Valley.”

“I felt my education was inadequate as compared to what my fellow shipmates received in the other part of the nation, specifically the ‘North.’ [M]y speech was definitely improved by these revelations. When my shipmates corrected my English to try and help me, I then quickly learned how to improve my speaking skills on my own,” wrote Longoria after his interview.

The G.I. Bill enabled Longoria to continue his education after his service. Upon his July 13, 1946, discharge at the rank of Seaman First Class, he finished high school in Brownsville, and then took a business administration course at a business college in nearby Harlingen.

After that, he took a job as a clerk in the Hidalgo County Clerk’s office in Edinburg, Texas. Unhappy with the pay there, however, he left the Valley to become an apprentice aircraft mechanic at the naval air base in Corpus Christi, Texas, where he stayed for one year.

He spent the next eight years as a mechanic for Pan American airlines in Brownsville, then was sent to San Francisco when the Brownsville plant closed. He didn’t like it there, however, so he soon began working for Dallas-based Braniff Airlines, which became part of Dalfort Corporation in the ‘80s. He retired from Dalfort in 1992 after 42 years as an aircraft mechanic.

After retirement, Longoria bought surplus tools from Army and Air Force bases and sold them at the flea market. At the time of his interview, he was a chairman of the Democratic Party’s Precinct 322. Inactive in politics prior to WWII, he said he’s “trying to help my people and my neighbors” through his activism.

Longoria married Gloria Waterbury on July 20, 1951. They have two sons and two daughters. Though he raised them to speak both Spanish and English, he says it was difficult to make the Spanish stick due to the small number of Spanish-speakers in the area of Dallas in which they lived.

When speaking to his oldest son in Spanish, for example, Longoria says he noticed that his son answered in English. When asked why, Longoria recalls his son replying, “It’s just too hard, Dad.”

Longoria’s advice to the younger generations is, “Stay in school and go to college. Finish and you’ll be better off. Education is power.”

He says he sees more opportunities now for Latinos in the U.S., and that he and Gloria have strived to give their children better lives than they had growing up.

“My father had a grocery store in Madero, Texas, but we lived in Mission. He, during the Depression, he went bankrupt. When my father went broke, he, of course, had to go work for somebody else,” said Longoria of his early years.

He reiterated that joining the Navy dramatically broadened his view of the world.

“I realized things weren’t right down there,” said Longoria of Texas’ isolated Rio Grande Valley region. “I learned a lot in the Navy and I’m so proud to have served. It did improve my life, and then, of course, I came back and went to school.”

Mr. Longoria was interviewed in Lewisville, Texas, on October 15, 2007, by Elizabeth Fisanick.